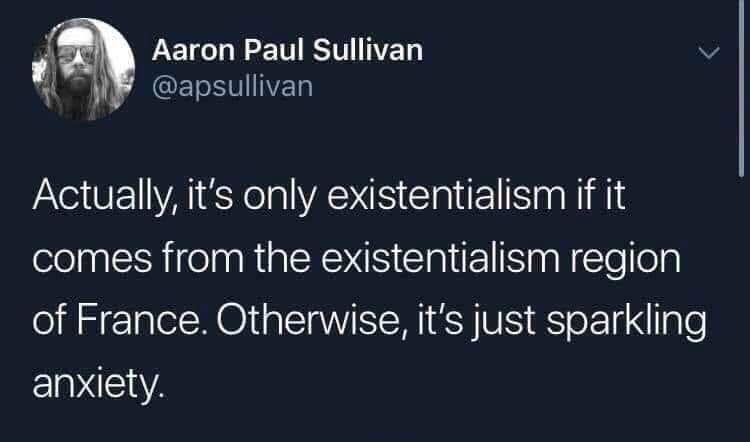

controlled designation of origin

local French person has aneurysm over what people get away with calling "ratatouille"

We’ve talked about this before in by changing the name, you changed the recipe: one of the defining features of French cuisine is, to me, how particular and intentional we are with the names and provenance of our food.

We have a whole nomenclature of AOCs, meaning Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (Controlled Designation of Origin), which guarantees a certain foodstuff was produced in a very defined geographical location (its terroir). This is why I don’t eat Somerset “brie”; it may well be perfectly nice soft cow cheese, but depending whether you’re measuring from Meaux or Melun, it’s approximately 650-700km away from the Brie region. Find your own dang soft cow cheese name.

And after maybe a year of not commenting on anything eaten off a board being called “charcuterie” on socials, I’ve decided it’s time to clear up a few misunderstandings about French food terminology.

I cannot stress enough how much I’m coming to this from a place not of superiority, but genuine cultural exchange. Just google “French tacos” and you’ll see what kind of unspeakable things we’ve done to other cuisines’ dishes without a shred of shame. In the case of charcuterie boards, I could not be happier about their trend status – I’ve loved seeing them on my friends’ table at house parties, on pub snack menus, and I’ve definitely taken notes from inventive ones I’ve seen online.

But in the case of charcuterie as a term, it just means cold cuts – it’s the name given to the process of preserving meat, and includes many regional varieties of saucissons, pâtés, hams. Only if you’re serving a collection of cold cuts on a piece of wood does it become a charcuterie board. If there’s only cheese or fruits or, god forbid, candy (an unfortunate sight that is burned onto my retinas), that’s still a board. Just not a charcuterie board.

It’s also been fun to see it raised to the status of sophisticated food. I need you to know it’s our most basic bar snack, and our most lazy group dinner. It’s our scampi fries, pork scratchings, bag of salt & vinegar chips splayed out in the middle of the pub table.

This has the same quality to me as the word pâtisserie coming to represent a particularly fussy form of pastry. Of course, France has its fair share of exclusive, expensive and labour-intensive pâtisseries. But to an average Jean like me, it evokes whichever bakery I’ll find on the next street corner to grab a quick dessert for my lunch break. Taking the Overground to go and queue for an “elevated” pain au chocolat in Shoreditch is a foreign concept to me. Again, not a bad one in nature – just a foreign one. My point is that I’ll have to live without a boulangerie-pâtisserie until London stops seeing it as sophisticated and starts seeing it for what it really is: our version of Greggs. What is it that makes pâtisserie sound fancy? Is it the little hat on the a?

Then, there’s the other side of the pedestrian-to-extravagant coin. Upon moving to the UK, I found out that the word “peasant” was much more like an insult than our “paysan”. Only a couple of pages into his book Puligny-Montrachet: Journal of a Village in Burgundy, Simon Loftus recounts a local vigneron’s description of the difference between Puligny and the other wine-making village on the other side of the hill: “Puligny is more bourgeois, Chassagne is more peasant.” It would be easy to read this as an attack on the backwards hicks over yonder, and yet, to a French person this is a simple observation. Loftus goes on to describe just how similar the villages actually are, and how equally dedicated to wine-making they are.

A paysan has intimate knowledge and understanding of the land they work and the animals they rear, a relationship with their terroir and craft dating back centuries. I’ve had some of my most decadent meals in peasant kitchens: my first taste of truffles, snout-to-tail and gill-to-fin tasting menus, salads made from a dozen different heirloom tomato varieties. No one knows food like the peasant who took it from the soil. The word carries a lot of pride, particularly for the people it describes, and in the cottage-core era we live in, not a little misplaced nostalgia.

It is especially jarring when that longing for the French provincial life curves so far it becomes a loop, and our need to name and protect everything becomes apparent. I’m talking of course about “chicken wine”, the La Vieille Ferme screw-top bottles going for seven quid at your Tesco Local. Despite its popularity and many raving reviews, I’m highly suspicious of a wine that lists no provenance of composition, and coasts on a hand drawing of hens and a line of script in French to appear paysan. The line, by the way, reads “bottled by the old farm” – by, not at. I refuse to try it. You don’t get to slap some twee imagery on the sticker of a wine simply labelled “red” and co-opt our borderline neurotic food culture.

Okay, I may have lied a bit earlier when I said this was coming from a place of cultural exchange. My next point comes from a place of boiling hot rage. I need everyone the world over to learn the difference between a tian and a ratatouille.

They come from the same region and mostly have the same ingredients: tomato, aubergine, courgettes, onions, herbs. But if I promised you a hamburger and instead served you a plate with a steak, a lettuce and tomato salad and a slice of cheese on a piece of bread, would you or would you not tell me to fuck off?

Fortunately, it’s a simple difference. If you cut the vegetables into slices and bake them, it’s a tian. If you cut them in chunks and stew them, it’s a ratatouille. Please read this paragraph three more times and know that you have contributed to my long-term health by helping to significantly decrease my blood pressure. Each time I have seen the below advert on a billboard, I have considered committing vandalism. Possibly arson.

Finally, I would like to end this rant on provenance and proper naming with a plea to the Americans among us: please stop calling them French fries. They’re from Belgium. We’ve been making fun of Belgians ruthlessly for centuries for no reason at all – our relationship is fraught enough as is. Please don’t throw more oil on the friteuse.

Greetings from the peasants 😘

Truffles!!!! 🤪